What the Narnia books can teach us about sharing our faith with reverence, honesty and joy

By Sue Careless

IF WE are to tell the Christian story of redemption in a more beautiful fashion, Michael Ward believes we must, like C.S. Lewis, “become alive to beauty in every context, the beauty of bread and butter, of the skies and everything in between.”

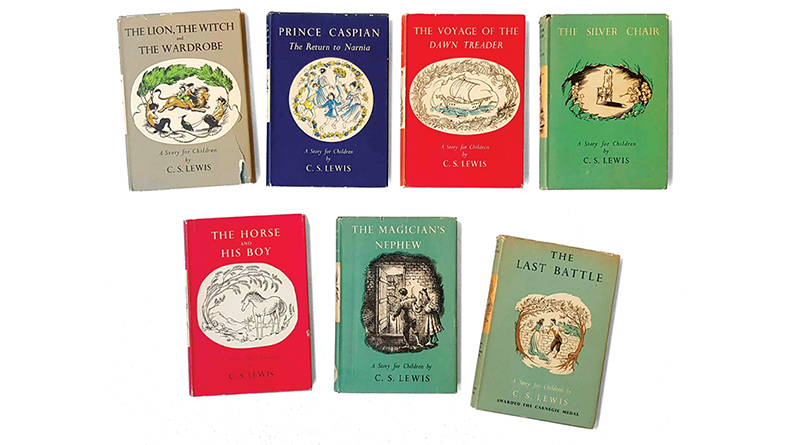

Ward was speaking at the Mere Anglicanism conference held in Charleston, S.C. in late January. The English literary critic and Oxford theologian is the author of the award-winning Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis. He also presented the BBC television documentary, The Narnia Code, and authored the accompanying book.

Ward thought that though Lewis was “sensitive to every kind of beauty, he wasn’t ever precious about it. He knew that if beauty was isolated and overvalued and made into a cultural standard of goodness and respectability, it ended up losing much if not all of its beauty.” Lewis’ essay “Lilies that Fester” made this point.

And Lewis knew that beauty could be used as a mask for evil. The White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, has a beautiful face, white as snow, but it was “proud and cold and stern.” In Prince Caspian, the lovely Lady of the Green Kirtle who had the “richest, most musical laugh you can imagine” shape-shifted into a green serpent and held Caspian under a wicked enchantment

Ward cited the witch Jadis in The Magician’s Nephew. “She was dazzlingly beautiful and Digory in his old age says he had never met a woman more gorgeous. Yet this same Jadis is a vain, manipulative, genocidal tyrant,” said Ward. “Beauty can be ruthless. John Keats said, ‘Beauty is truth; truth is beauty.’ Not so fast says Lewis. Beauty can be put in the service of very bad ends.”

Lewis knew that beauty “can be abused in two different directions,” said Ward. “It can become idolatry if we fixate upon the channel of beauty rather than the transcendent quality to which it points. And it can become a kind of prostitution if we abuse other people’s desire for beauty in order to achieve our own purposes over them.”

Ward believed that Lewis in his various writings told the Christian story with “reverence, with honesty and with profound joy.” This would follow from Peter’s exhortation in his first epistle: “in your hearts honour Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defence to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect…” (3:15). So, we begin with a reverence for Christ but also a respect for those we are addressing. Ward warned that “We don’t bombard them with more than they can take in. We speak to their condition if we can.”

Ward said that we also need to have a gentleness and reverence toward the very message we’re trying to communicate: “Beauty that is easily articulated is cheap, glib. If we talk about it too quickly, is that a sign that we’ve not really encountered it? It should produce in us a kind of holy reticence. We shouldn’t short-circuit the process by putting it into words too hastily…. Hold your silence. There is a holy ritual being undertaken. Chatter is out of place.”

In The Weight of Glory Lewis speaks of our own desire for the “far-off country,” the transcendent. “We feel in ourselves a certain shyness…a desire for something that has never actually occurred in our experience…”

Surprised by Joy is Lewis’ spiritual autobiography. He had been an atheist in his youth but he records becoming a deist in the penultimate chapter. Ward describes that as “a big, noisy moment. Lewis describes being ‘dragged kicking and screaming into the kingdom of God, the most reluctant convert in all of England.’ Yet this is the term used for his theistic conversion not his Christian conversion. His Christian conversion is much less obvious, quieter, more understated. He calls it ‘Almost Eden.’ He doesn’t herald it with drums and whistles. That would cheapen it and vulgarize it.”

Yet by no means is Lewis suggesting that Christianity is too important to talk about,” said Ward.

It is true that Lewis’ memoir, A Grief Observed, which was written after the death of his wife, was penned under a pseudonym and only came out under his own name after his death.

“This would partly be because of his own personality, his native British reserve and his academic context but some of his reserve is grounded in a very proper reverence,” said Ward. “Treat the treasure of faith too roughly and you may desensitize yourself to the sacred value of what you are trying to communicate.”

We see a holy reticence in The Horse and His Boy when Shasta encounters Aslan in the mountains, except at first Shasta doesn’t know it’s Aslan breathing on him in the mist and in the dark:

Shasta “couldn’t say anything but then he didn’t want to say anything. And he knew he needn’t say anything.”

“If that isn’t a prime example of telling a more beautiful story, I don’t know what is,” said Ward. “Aslan retells Shasta’s story to him in ways that leave him simply awestruck. Actions speaks louder than words. What passes between the divine lion and the lonely little boy is one of the greatest passages Lewis has ever written.

“Let us tell this beautiful story [of the gospel] with care and reserve and with circumspection.”

Ward also drew out the necessary paradox of both pain and joy in the Christian story and how carefully they must be balanced:

“The beauty of the gospel will be diminished if there is not pain involved or if there is excessive concentration on the pain. Likewise if there is no joy involved or there is excessive concentration on the joy. Christ dies on Good Friday and rises on Easter. We die to sin and rise to new life. The two are inseparable in the telling of the story but not indistinguishable.”

Pilgrim’s Regress (1933) was the first book Lewis wrote after his Christian conversion and it is bittersweet. It is modeled in part on John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), a book Lewis said, “startled the world.” Lewis’ protagonist John has visions of a far-off island that fill him with indescribable yearning. Ward cited this passage:

“There came to John from the wood a sweetness and a pang so piercing that he completely forgot his father and his mother and the Landlord and the rules. All the furniture of his mind was taken away. A moment later he found he was sobbing. The sun had gone in and what had happened to him he could not quite remember.”

There is pain and beauty and an allusion to Psalm 45:10, “Forget thy people and thy father’s house.….” Writing about Psalm 45 in Reflections on the Psalms, Lewis notes that the exhortation to the bride to forget her father’s house is an allegory. Lewis writes: “The Bride is the Church. A vocation is a terrible thing. To be called out of nature into the supernatural life is… a costly honour.”

Ward also compared John’s situation in Pilgrim’s Regress to God’s call to Abraham in Genesis 12 when the patriarch is told to leave all that he knows. “It’s a terrible command. Turn your back on all you know. There are consolations: the embrace of the divine spouse, the fruitfulness that results from those embraces. But those consolations don’t cancel or eradicate those real privations. So that is how John’s pilgrimage begins, a poignant comingling of joy and sorrow.”

How does John’s pilgrimage end? “The island was different from his desires and if he had known, he would not have sought it.”

There is no question that John, the pilgrim, has been deceived but, said Ward, “Thanks be to God for deception because how could John have desired holiness in his natural state? Grace gives John unmerited reward but also the capacity to enjoy it.”

Apparently, Lewis didn’t think highly of the conversion moment in Bunyan’s story when Christian, the pilgrim standing at the foot of the Cross, loses his heavy burden of sin, which then rolls down the hill into the open mouth of a sepulchre.

Lewis thought more highly of the scene in the Valley of Humiliation which he said was the most beautiful thing in Bunyan “and the most beautiful thing in life if a man takes it quite rightly.”

“If the story becomes all sweetness and light the story becomes saccharine and fluffy,” said Ward. “It loses its poignancy and substance. Coming to know God, in Lewis’ phrase, is ‘a sweet humiliation’ and a blessed defeat. Retain both elements honestly and the picture you paint will be all the more beautiful.”

Lewis never forgets this as he tries in his various retellings of the Christian story to bring to a climax a terrible thing and a beautiful thing more or less simultaneously.

In The Great Divorce we are told that when one man is freed from the lizards of lust, his face “shone with tears.”

In That Hideous Strength the remaking of Jane’s soul went on amidst “a kind of splendour or sorrow or both.” Why sorrowful? Isn’t it just splendid? Ward explains: “It’s sorrowful because Lewis is honest enough to recognize there is pain in being divorced from our sins, leaving behind our natural attachments.”

In a 1952 letter, Lewis sent both his congratulations and condolences to a woman with whom he’d had a long correspondence and who had recently become a Christian. He believed that an adult conversion is not without its distresses. “Indeed, they are the very sign that it is a true initiation.”

In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader Eustace Scrubb tries three times to shed his dragon skin but each time the schoolboy-turned-dragon finds himself still trapped by his own selfish greedy nature. Ward said, “Only when he lies back to be undressed by the Lion does he feel a claw deep into his heart to lob off the thick dark, knobbly hide.”

Ward believes Christ’s own journey is the “template from which all accounts of conversion must be cut.” This divine pattern is a V-shaped narrative. If we have died with Christ, we believe we will also live with him. This V-shape is clear in Paul’s exhortation to the Christians in Philippi to have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

6 Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; 7 rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. 8 And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death – even death on a cross!

9 Therefore God exalted him to the highest place and gave him the name that is above every name, 10 that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Philippians 2:6-11)

In The Silver Chair Jill and Eustace flee their wretched boarding school and enter Aslan’s country. Then accompanied by Puddleglum, they enter Narnia, and go down deep into Underland, and deeper still into Bism. But after accomplishing the difficult task which they were assigned, they navigate a dangerous route in almost total darkness that leads them back up again into Narnia, and later home to England.

“There must be this basic shape in all presentations of the gospel, said Ward. “Down, down further, then up and up higher than before but having accomplished something new and unchangeable.”

There is joy in the gospel story but often “joy and sorrow flow mingled down” as the old hymn says. To illustrate, Ward read this poignant passage from The Magician’s Nephew:

“’Please, please,’ says Digory, ‘can’t you give me something that will cure Mother?’ Up till then he has been looking at the Lion’s great feet and huge claws; now in his despair he looked up at its face. What he saw surprised him as much as anything in his whole life. For the tawny face was bent down near his own, and (wonder of wonders) great shining tears stood in the Lion’s eyes. They were such big, bright tears, compared to Digory’s own that for a moment he felt as if the Lion must really be sorrier about his Mother than he was himself.

“My son, my son,” said Aslan, “I know. Grief is great. Only you and I in this land know that yet. Let us be good to one another.”

There is a similar moment in The Silver Chair when Aslan wept great Lion-tears over the body of King Caspian “each tear more precious than the Earth would be if it were a solid diamond.” Then he commands Eustace to drive a thorn as sharp as a rapier into his paw. Eustace obeys and as a huge drop of blood splashes over the body of the dead king, he is brought back to life.

“These are beautiful moments but they are only moments in fictional stories and in Christ we turn from fiction to reality,” said Ward. “The glorious truth is that Lewis was able to weave such beauty into his stories because it was a reality he knew in his spiritual life, and especially in his experience of Christian worship. ‘Our most joyous festivals,’ Lewis wrote, ‘centre upon the broken body and the shed blood and there is thus a tragic depth in our worship which cannot and must not be avoided. Our joy has to be the kind of joy that can coexist with that.’”

Ward concluded his presentation saying: “With joy, honesty and reverence Lewis told and retold the beauty of the story of redemption and not just in art but in fact, in the way he lived his life. And the way he responded to God’s love with his own love and worship and service. May we go and do likewise.” TAP