By His Wounds We are Healed

By Michael Ward

PERHAPS GOOD FRIDAY should be called Good Death Day as it would keep before us the paradox of what is going on.

What good is any crucifixion, especially this crucifixion? Christ’s crucifixion was not good in and of itself. It was the bitter fruit of betrayal, folly, political expediency, injustice, scorn, bloodlust.

What brought sweetness, goodness out of it was that miraculously it was entered into freely out of love. So, we can say it was the most heinous act in the history of the world and at the same time the salvation of the world. The spear in Christ’s side is–at the same moment–a shattering of perfection and the means by which perfection perfects the imperfect.

Forgiveness doesn’t pretend there is nothing to forgive. Forgiveness is not the same as selective amnesia, turning a blind eye to the wrongs that have been committed. That would just be injustice. The victims would remain crying to heaven. Forgiveness honestly recognizes sin, looking at it steadily and yet saying, someone has paid a price for this sin. And he’s able to pay it out of his infinite wealth. And from his riches I can draw a little sum of magnanimity. I can draw a little in order to forgive the particular sins that have been committed against me. Thus, the debt is paid. “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed,” (Ps. 85:10).

Forgiveness cancels the penalty of sin but not the cost of forgiveness. A real price has really been paid. We know this because the risen Christ bears in his body the marks of the nails and the wound from the spear. As Revelation tells us, Jesus is “The Lamb slain from the foundation of the world” (Rev. 13:8). Jesus goes through death, down, down then up the other side to a new kind of life that doesn’t erase the suffering but is able to incorporate it. His wounds remain visible in heaven, confirming that the forgiveness he enables is real and making the Easter joy all the more profound. Remember the verse in Matthew Bridges’ hymn, “Crown him with many crowns”:

Crown him the Lord of love;

Behold his hands and side,

Rich wounds yet visible above

In beauty glorified;

Thomas Aquinas and the Church Fathers agree that the wounds are not defects in Christ’s risen body but increase his glory and beauty, as trophies of his power and victory over sin and death.

And these wounds will have a central place at the Last Judgment fulfilling the prophecy of Zechariah that all people will one day see the one whom they have pierced (12:10). For those who have chosen to resist Christ’s grace, the wounds will serve as a condemnation. Aquinas quotes St. Augustine of Hippo, “Behold the man you have crucified. See the wounds you have inflicted. Recognize the side you have pierced, since it was opened by you and for you, yet you would not enter.”

Aquinas says that those who receive Christ’s grace, the saints, take their glorified life from him while he takes guilt and death from them. And the wounds testify to the reality of this exchange.

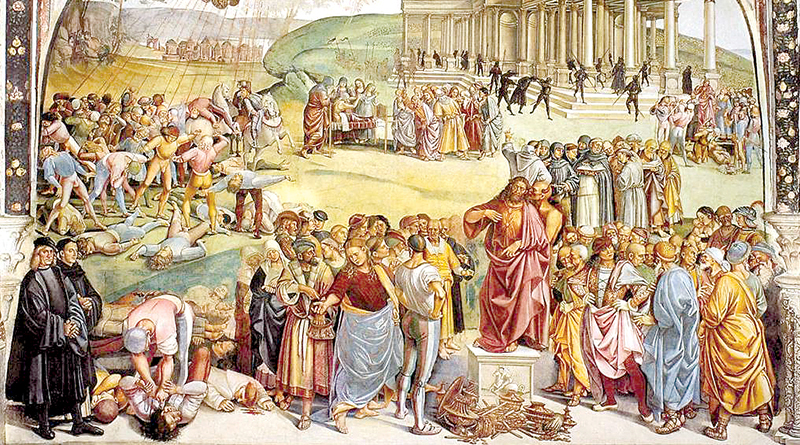

There is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Luca Signorelli called “The Sermons and Deeds of the Antichrist.” How do we know he is the Antichrist? Because he is pointing to his heart to claim how much he loves mankind, but the hand by which he points to his heart bears no wounds. It is actually the hand of Satan poking his hand through the cloak of a puppet figure. The Devil is the father of lies. But the one lie that the Devil can’t pull off is that he died and rose again from the dead because he has no wounds to prove it.

An honest telling of the Christian story will never gloss over these wounds. In a way the wounds on the body of the risen Christ are a symbol, a short-hand for the whole Christian story. They are wounds that are healed but they never disappear.

C.S. Lewis tells the Christian story with reverence, honesty and profound joy. In The Weight of Glory, he writes:

“The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them. It was not in them. It only came through them. And what came through them was longing.”

Lewis says longing came through these things, not beauty. Whose longing? If it’s our longing for God then surely it would make better sense to say ‘what went through these things was longing.’ What goes from us to God. Yet the longing comes through these things, which implies that it is God’s longing for us.

God’s longing for a loving relationship with his Creation is the longing that comes through the things that we find so beautiful. That’s why we find them so beautiful. In other words, remarkably, God finds us at least as beautiful as we find him. What greater cause for joy could be imagined?

Gregory of Nyssa, the great bishop and theologian of the fourth century, understood Christ’s words from the cross, “I thirst,” not just in a literal, physical sense but spiritually, relationally. The Lord is saying, ‘I thirst to be thirsted for. I want to be loved by those I love so much.” He longs to be longed for. That’s why he is going to this extremity of love.

As Lewis puts it in The Problem of Pain, “We were made not primarily that we may love God, although that is true, but that God may love us. “Crown him the Lord of love.” But what does that mean? What does it mean to love?

According to Lewis in The Four Loves, to love at all is to be vulnerable. Now without infringing on the truth of God’s impassibility, which is a very important doctrine, we can none the less say, the Lord Jesus in his sacred humanity can and does indeed become vulnerable. He weeps for Lazarus. He thirsts by the roadside asking the woman at the well for a drink. He agonizes in the garden of Gethsemane, with sweat coming like drops of blood. He dies.

To love at all is to be vulnerable. The Lord has broken open his own heart to us in love and in grateful, joyful response, we can do the same in return.

In one of his letters Lewis wrote: “The great allegorical sense of Mary Magdalene’s great action dawned on me the other day. The precious alabaster box which one must break over the holy feet is one’s heart. The contents become perfume only when it is broken.” TAP

The Rev’d Dr. Michael Ward is an English literary critic and theologian and the author of Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis. He presented the BBC television documentary, The Narnia Code, and authored the accompanying book. This is a portion of the talk that he gave on Jan. 27 at Mere Anglicanism in Charleston, South Carolina.