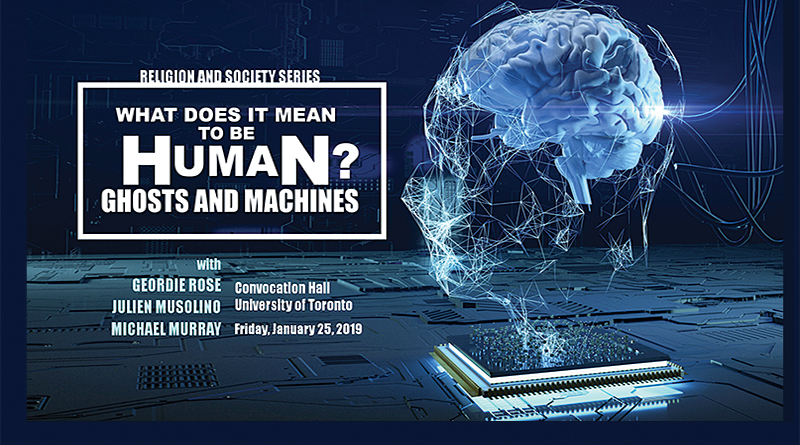

What Does it Mean to be Human? Ghosts in Machines

Comment by Tim Perry

ON JAN. 25th, over 600 people gathered at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall to hear a guided conversation around the question, “What does it mean to be human?” The event was also livestreamed to twenty sites across Canada.

The latest in the Religion and Society Series, this question follows naturally from those previous: God and the Origins of the Universe (2016), Science and the Existence of God (2017), and Three Perspectives on the Meaning of Life (2018).

Led by Wycliffe College, the evangelical Anglican seminary at the University of Toronto, the series organizers are diverse. Faith Today, the flagship publication of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, stands alongside Ravi Zacharias International Ministries (RZIM), Power to Change, and the Network of Christian Scholars representing a variety of Christian communities. The Centre for Inquiry Canada and the University of Toronto Secular Alliance were sponsors from a secular perspective.

This year’s speakers continued to reflect that diversity.

Noted Christian philosopher, Dr. Michael Murray, Executive Vice-President of the John Templeton Foundation, took the floor first to make three related claims. First, he argued that minds are more than simply organic computers and contrasted intention and understanding with effective information output to make his case.

Second, he claimed that recent findings in the mind sciences have both narrowed and – surprisingly – hardened the gap between human beings and other mammals. That is, on one hand, it is now demonstrable that humans share far more with other animals than was thought, say, a century past. On the other, however, it is also scientifically demonstrable that humans are capable of doing more with what is shared and that human beings can perform some mental tasks that simply have no counterpart elsewhere in the natural world.

Third, he concluded that the mind sciences do not require the rejection of what he called “non-physicalism. ” He rejected the idea that the mind can be accounted for entirely by physical or biological processes. He noted here a diversity of positions within non-physicalism, some more compatible with the current state of affairs in the mind sciences than others. He highlighted the inability of physicalism to account for concepts that, while not empirically verifiable, are nevertheless taken for granted by all people: free will and understanding.

Self-proclaimed “villain of the evening,” Rutgers University professor and cognitivist scientist Dr. Julian Musolino followed Dr. Murray to argue that “the Soul” was, simply, a fallacy. Neuroscience, he insisted, had failed to establish the existence of a soul on empirical grounds and therefore, the soul did not exist.

The contrast with the previous speaker was striking. Where the philosopher relied on evidence – much of it straightforwardly empirical – and argument to make his case, where he freely acknowledged weaknesses in his own position, and where his manner of delivery was quiet, inviting listeners to find force in the material rather than the manner of presentation, Dr. Musolino was the opposite. With the verve of an old-time revivalist, he asserted continually that “the traditional soul” was a fallacy without defining what a traditional soul is and all the while conflating the notions “scientific” and “empirical.”

The contrast with the first presentation was striking: passion-as-proof, rhetorical excess, straw-manning, question-begging were all evident in the scientist’s talk while empirical evidence, humility, logic and willingness to engage with contrary positions were amply present in the philosopher’s.

By far the most interesting (and at points genuinely frightening) talk, however, came from Dr. Geordie Rose, a pioneer in quantum computing technology and artificial intelligence. The founder and CTO of D-Wave, a quantum computing company, Rose presented the post-human vision of the near future. Rather than think of the soul as a substance that either exists or not, Rose challenged the audience to think of the soul as a pattern in our brains – a pattern that may well one day be simply an accepted part of artificial intelligence (AI). Souls – whatever pattern that term designates – will one day be built.

At its present stage, AI is comparable to a child and human beings are its parents. There is no reason, however, Rose claimed, to assume that AI will remain there. AI is on the verge of entering into its “adolescence” and beginning to think for itself. The intentionality gap described by Dr. Murray will be overcome and the future opened to post-humanism. The question humans must now face is just what we want our post-human future to look like.

Journalist Karen Stiller, senior editor of Faith Today, moderated the two-hour debate and helped generate some lively discussion among the speakers. The evening ended with questions from the floor. The most striking admission in these exchanges came from Dr. Rose who accepted, based on “the deep physics,” the physicalist contention that free will was an illusion. This in itself is hardly surprising. What did raise my eyebrows was his immediate concession that free will was a necessary illusion. Free will, he said, guaranteed the rule of law and accountability for one’s actions; it was a “myth” without which society would collapse. Dr. Rose’s change in pronouns was telling: we need the myth. I don’t believe it.

By the conclusion of the evening, I was convinced that the most important critical reflection taking place over the next two decades will have to do with the interface between human beings and technology, and especially between human bodies and technology. If souls “exist” as patterns of brain activity that will eventually be replicated and/or uploaded, what does that say about human beings as embodied souls or ensouled bodies? Are bodies soon to be disposable?

Ironically, though he did not believe in the soul or in free will, Dr. Rose sounded very much like an early second-century gnostic in his hope for a post-human (that is, post-body) future. And the speaker best able to engage with and challenge his project was not, ironically enough, Dr. Musolino, the neuroscientist, but Dr. Murray, the philosopher.

“Souls don’t exist!” apparently, is so last century.

The full debate can be viewed at https://youtu.be/ 2IYR22ouDP8. TAP

Dr Tim Perry is the theological editor of The Anglican Planet.

A Few Definitions

Mind Sciences: Various disciplines, e.g., neuroscience, biology, psychology, physics and computation that address the mind-brain or soul-brain relationship in their field of study.

Neuroscience: An umbrella term taking in those disciplines that study the structure and function of the brain and nervous system.

Artificial Intelligence (AI): computer systems designed to perform tasks traditionally associated with uniquely human activity, e.g., language translation. (Have you used Google Translate lately?)

“The Ghost in the Machine”: Coined by 20th-century philosopher Gilbert Ryle to both summarize and scorn Rene Descartes’ sharp distinction between the mind/soul and the brain. Ryle was convinced that mind or soul could be accounted for purely in physical terms.

Physicalism: The conviction that mind or soul can be accounted for entirely in physical or material terms. What we call “mind” is merely advanced brain activity that ceases at brain-death.

Non-physicalism: The conviction that mind or soul cannot be accounted for entirely in physical or material terms. Belief in an immortal soul (as in Plato or Descartes) is one of several “non-physicalist” options.