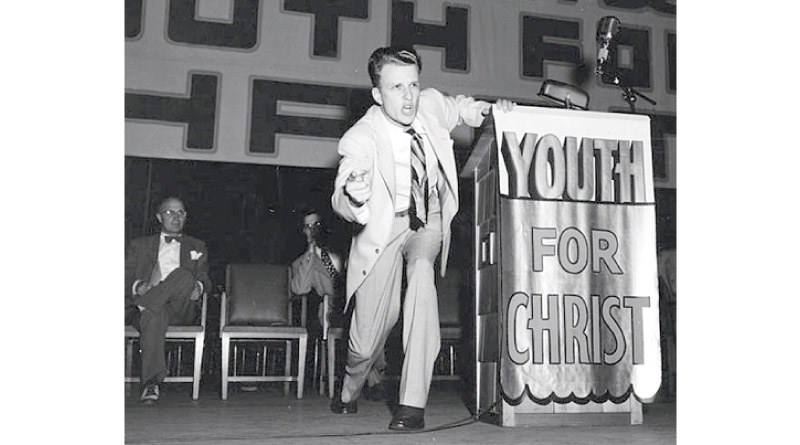

Tribute: Billy Graham, Evangelist (1918-2018)

By Sue Careless

THE MAN dubbed ‘America’s pastor’ and ‘the Evangelist to the world’ died on Feb. 21 at the age of 99. It is estimated that over six decades Billy Graham preached to 215 million people (face-to-face and by satellite feed) in more than 185 countries, an effort that resulted in millions of conversions.

How did a farm boy from North Carolina with no advanced degree in theology have such a global impact?

While attending Florida Bible Institute in Tampa, Graham would rehearse his sermons in the nearby swamps, preaching to the alligators. Little did he know then that in 1973 he would address 1.1 million people in Seoul, South Korea. He became a true fisher of men.

His 417 missions between 1947 and 2005 were no hit-and-run affairs either. His longest crusade took place in New York City in Madison Square Garden in 1957 – it lasted 16 weeks.

No matter in what city he spoke – Los Angeles, London, Paris, Berlin, Toronto, Moscow, Hong Kong Tokyo, Buenos Aries, Shanghai – it was at the invitation of the local churches. There were months of preparation beforehand with these congregations. He led 13 missions in nine Canadian cities.

At each rally Graham preached a simple, direct gospel message to thousands of people. He certainly struck a fine figure, with his Hollywood good looks and his baritone voice but those in the crowd would say they felt that he was talking to them alone. His personal conviction and sincerity seemed to ring true.

After preaching he always offered an ‘altar call’ – a chance for those in the stadium to come forward and commit or recommit their lives to Christ. Those who did so then met with volunteer counsellors from the local churches who prayed with them and gave them a Gospel of John or a Bible study booklet. Moreover, the crusade connected them to a local church so they were not left spiritually stranded after the rally ended.

In Moscow, in 1992, one-quarter of the 155,000 people in Graham’s audience went forward at his call. He was welcomed even by repressive leaders like Kim Il-sung of North Korea, who invited him to preach in Pyongyang’s officially sanctioned churches.

America had known other popular evangelists who could draw vast crowds but Graham took advantage of jet travel and satellite communications. In 1986, in Paris, he used direct satellite transmissions to carry his sermons to about 30 other French cities. In 1995 during his “global crusade” from Puerto Rico, his sermons were translated simultaneously into 48 languages and transmitted to 185 countries by satellite.

Race & Politics

Although a white southerner – both his grandfathers had been confederate soldiers – Graham spoke to racially mixed crowds and allowed blacks and whites to mingle during the altar calls even before desegregation. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. publicly credited Graham with helping the cause of civil rights.

However, in an interview with The Associated Press in 2005, when he held his final mission, Graham said he wished he had fought for civil rights more forcefully. In particular, he regretted not joining King and other pastors at voting rights marches in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

“I think I made a mistake when I didn’t go to Selma,” Graham said. “I would like to have done more.”

But he thundered at his rallies “Christianity is not a white man’s religion. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s white or black. Christ belongs to all people.”

He was also a ‘pastor to presidents’ and said that “with one exception, I never asked to meet with them. They always asked to meet with me.”

He also offered prayers at a service in the National Cathedral for victims of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. After these attacks he called his rallies ‘missions’ not ‘crusades’ so as not to offend Muslims. In 2006 he preached in New Orleans to Hurricane Katrina survivors.

Although he was a confidante of both Republican and Democratic presidents, he never endorsed any political candidate, with the exception of Richard Nixon. Nor did he support groups like the Moral Majority. He avoided addressing controversial topics that might divide his audience. “I’m just promoting the gospel,” he said in an interview in 2005.

In 2002 Graham issued a written apology and met with Jewish leaders after an anti-semitic remark that he had uttered three decades earlier and that had been captured on tape by Richard Nixon came to light.

He also regretted not having studied or prayed more.

Anglican & Catholic Friends

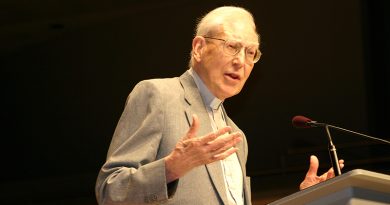

Initially the liberal Protestant churches denounced the Southern Baptist pastor as a fundamentalist but he distanced himself from any such fundamentalism and identified as an evangelical. He became a close personal friend of John Stott, the evangelical Anglican theologian, and was greeted warmly by C.S. Lewis, the Anglican apologist and writer, when he visited England.

Stott and his church, All Souls, Langham Place, supported Graham during his astounding London crusade in 1954, which captivated the city nightly for nearly three months. Over the next 50 years, the two men remained close personal friends and shared leadership in such significant ventures as the Lausanne International Congress on World Evangelization.

Canadian Anglican theologian J.I. Packer, then a layman in England, recalled hearing Graham address 750 English church leaders in 1952 as they assessed whether to invite him to lead a London crusade. Packer told Christianity Today:

“[Graham] was relaxed, humble, God-centered, with a big, clear, warm voice, frequently funny and totally free from the arrogance, dogmatism, and implicit self-promotion that, rightly or wrongly, we Brits had come to expect from American evangelical leaders. He was engaging in his style, displaying the evangelist’s peculiar gift of making everyone feel that he was addressing them personally.”

Two days later the leaders invited Graham to lead what Packer describes as “by far the most momentous religious event in 20th-century Britain.” Packer added, “Graham’s British breakthrough was the first step on a truly global ministry.”

Queen Elizabeth invited him for private audiences and asked him to preach at a palace chapel. In 1981 Pope John Paul II embraced Graham and said, “We are brothers.”

Family & Finances

Raised in a Christian home in Charlotte, North Carolina, Graham initially wanted to be a baseball player but in 1934, at the age of 16, he attended a local revival meeting at which he answered the altar call. “I did not feel any special emotion,” he wrote in his 1997 autobiography, Just As I Am. “I simply felt at peace.”

At 22, Graham met his wife Ruth Bell at Wheaton College, a Christian liberal arts school in Illinois. She was the daughter of medical missionaries in China and hoped that as a couple they too would serve overseas. Instead Ruth raised, often single-handedly, their five children in North Carolina while her husband spent months at a time preaching out of state or abroad.

Later Graham said one of his greatest regrets was that he had not spent more time with his family. Yet their marriage endured and all of their children and two of their grandchildren serve in Christian ministry. On his 77th birthday, Graham named his elder son, Franklin, his successor as head of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA).

Graham was never sullied with the sexual or financial scandals that destroyed the ministries of other evangelists of his generation. He made a point of never being alone with a woman other than his wife and she remained faithful to him despite his long absences.

The BGEA paid the evangelist a modest salary and he lived in an unassuming home in the mountains of North Carolina. At the end of each rally BGEA would publish their finances in the local media for public scrutiny. Their books were always open.

In recent years Graham had to contend with prostate cancer, hydrocephalus and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Yet he continued to write, publishing over 30 books in all. In the last, The Reason for My Faith (2013) he wrote:

“Buddha never claimed to be God. Moses never claimed to be Jehovah. Mohammed never claimed to be Allah. Yet Jesus claimed to be the true and living God. Buddha simply said, ‘I am a teacher in search of the truth.’ Jesus said, ‘I am the truth.’ Confucius said, ‘I never claimed to be holy.‘ Jesus said, ‘Who convicts me of sin?’ Mohammed said, ‘Unless God throws his cloak over me, I have no hope.’ Jesus said, ‘Unless you believe in me, you will die in your sins.’”

Graham died at his home in Montreat, N.C. but his body lay in state in Washington, D.C. His wife Ruth had died in 2007 and Graham was buried beside her in a simple pine casket made by inmates at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where he once preached. TAP