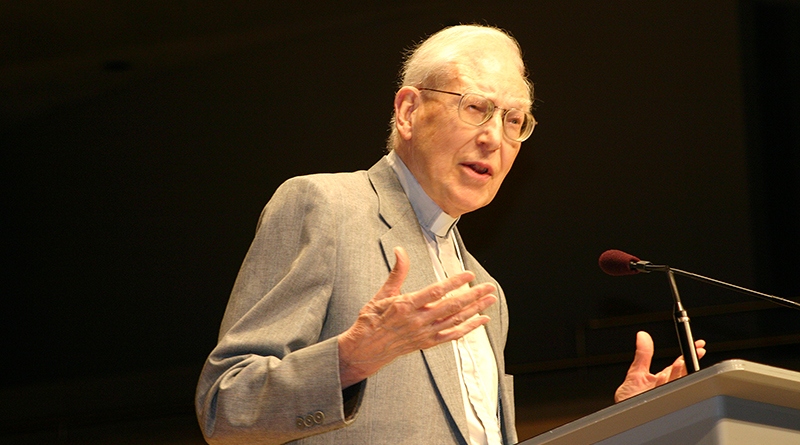

Tribute: J.I. Packer 1926-2020

By Sue Careless

ONE OF THE MOST influential evangelicals in the English-speaking world died on July 17, just shy of his 94th birthday.

Canon Dr. J. I. Packer was an English-born theologian in the evangelical Anglican and Reformed tradition who during the last half of his adult life called Canada his home.

A prolific writer of almost 70 books, he is probably best known for the spiritual classic, Knowing God (1973).

In its foreword Packer wrote: “As clowns yearn to play Hamlet, so I have wanted to write a treatise on God.” In his self-effacing manner, he said it was “at best a string of beads” but for millions of readers around the globe, Knowing God was indeed a veritable treatise on God, and a spiritual treasure. He wanted it to be a practical road map for travellers, not for onlookers on balconies only theorizing, watching pilgrims passing below.

“Thus (for instance) in relation to evil, the balconeer’s problem is to find a theoretical explanation of how evil can consist with God’s sovereignty and goodness, but the traveller’s problem is how to master evil and bring good out of it.”

The scholar believed that theology should lead to doxology [praise]: “Any theology that does not lead to song is, at a fundamental level, a flawed theology.”

Packer was deeply influenced by the works of John Calvin and the English Puritans and brought seventeenth-century Puritan devotion to life for both his students and his readers. In 2005 he was named as one of the 25 Most Influential Evangelicals by Time Magazine.

One of his biographers, Leland Ryken, noted that “Although Packer could write specialized scholarship with the best, his calling was to write mid-level scholarship for the layperson… he regarded his informal theological writings for the layperson to be his calling.”

Beginning in 1958 Packer authored no fewer than 47 books. His last published was Finishing Our Course with Joy (2014). He coauthored another 17 books, and published five collected works so you would need several bookshelves to hold all his tomes.

He considered his role as general editor of the English Standard Version (2001), an evangelical revision of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, as one of his greatest contributions to the global church. He was also theological editor of the ESV Study Bible (2008).

Packer had a significant influence on American evangelicals since he served for more than 30 years as senior editor and visiting scholar for Christianity Today. When the magazine conducted a survey to determine the top 50 books that have shaped evangelicals, Packer’s Knowing God came in fifth.

James Innell Packer was born on July 22, 1926 in Gloucestershire, England, the son of a railway clerk and a homemaker. He had hoped for a bicycle on his eleventh birthday but providentially, as it turned out, was given a typewriter instead.

Growing up in a nominal Anglican home, Packer attended church and was confirmed at 14. As a teen he read C.S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters, and Mere Christianity as well as his grandmother’s copy of the King James Bible. But he became a committed Christian at 18, largely through the Oxford Inter-Collegiate Christian Union and St. Aldate’s Anglican Church.

He had won a scholarship to the University of Oxford, where in 1954 he obtained a Doctor of Philosophy in theology. He wrote his dissertation on Puritan Richard Baxter’s doctrine of salvation. “It was the Puritans,” Packer noted, “that made me aware that all theology is also spirituality.”

He was ordained a priest in 1953 in the Church of England and a year later married Katherine “Kit” Mullet, a Welsh nurse to whom he was devoted. She proved a mainstay to Packer’s domestic life, and a source of constant encouragement.

He served as an Assistant Curate in Birmingham for three years but more of his professional life was spent at the typewriter or in the lecture hall than in the pulpit. He taught at Tyndale Hall, Bristol from 1955 to 1961. For the rest of the 1960s he was Librarian and then Principal of Latimer House, Oxford – an evangelical research centre established by Packer and John Stott to strengthen the theological foundation of the Church of England.

In 1970 Packer became Principal of Tyndale Hall, Bristol, and from 1971 until 1979 he was Associate Principal of Trinity College, Bristol.

Although Packer did not court controversy it came his way. In 2015 he remarked, “I should like to be remembered as someone who was always courteous in controversy, but without compromise.”

In 1966, the three most notable British evangelicals were the Welsh independent minister Martyn Lloyd-Jones and the Anglicans, Stott and Packer. At the National Assembly of Evangelicals in London that year, Lloyd-Jones called on evangelicals to come out of denominations in which they were “united with the people who deny and are opposed to the essential matters of salvation.”

Stott and Packer clashed publicly with Lloyd-Jones, rejecting his bid for a unified British evangelical church. They organized the first Evangelical Anglican Congress at Keele a year later, publicly committing to full participation in the Church of England. When Packer co-authored Growing into Union in 1970 with two Anglo-Catholics, Lloyd Jones broke formally with Packer, ending the Puritan Conferences that they had co-founded and then hosted for nearly two decades.

The authority and reliability of Scripture had been a central theme in Packer’s work since he published his first book, Fundamentalism and the Word of God, in 1958. It came as no surprise when he signed the famous Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy twenty years later, affirming a conservative position on the issue.

Packer’s willingness to work with Roman Catholic Christians would lead to a clash with the Chicago Statement’s primary author, R. C. Sproul, and other conservative evangelicals in 1994, when he partnered with Richard J. Neuhaus as a leader of Evangelicals and Catholics Together. The group’s founding statement affirmed significant doctrinal agreement and called for cooperation in evangelism and cultural renewal in the face of a rising secularist tide.

In 1979 Packer was invited by James M. Houston, the founding principal of Regent College in Vancouver, to join the faculty. (Houston had been an Oxford don when Packer was a student.) Packer accepted the invitation and was eventually named the first Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology, a title he held until he was named a Regent College Board of Governors’ Professor of Theology in 1996.

He was also a key figure in the Essentials movement within the Anglican Church of Canada, which was attempting in the 1990s to renew theological orthodoxy within that denomination. Packer spoke to 700 Anglicans at the formative Essentials ‘94 conference held in Montreal, and his address was published as a chapter in the book Anglican Essentials (1995).

The conference also produced The Montreal Declaration. Packer played a central role in its composition.

In Vancouver, Packer and Kit joined St. John’s (Shaughnessy) Anglican Church, which, with 800 members, was the largest congregation in the Anglican Church of Canada. However, in 2002, when the synod of the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster in Vancouver authorized its bishop to produce a service for blessing same-sex unions, Packer was among the synod delegates who walked out in protest.

“[T]his decision, taken in its context, falsifies the gospel of Christ, abandons the authority of Scripture, jeopardizes the salvation of fellow human beings, and betrays the church in its God-appointed role as the bastion and bulwark of divine truth.”

He also explained: “For many decades now, I have asked myself at every turn of my theological road: Would Paul be with me in this? What would he say if he were in my shoes? I have never dared to offer a view on anything that I did not have good reason to think he would endorse.”

In February 2008, the congregation voted overwhelmingly to leave the ACC altogether and realign with the newly-formed Anglican Network in Canada (ANiC). On April 23 of that year, Packer handed in his licence to Michael Ingham, the Bishop of New Westminster. The Anglican Network in Canada would subsequently join the Anglican Church in North America.

Packer served as theologian emeritus of the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) since its creation in 2009, being one of the nine members of the task force that authored Texts for Common Prayer, released in 2013.

Packer was keen to see the North American church recover catechesis or instruction in the Christian faith. To that end he was delighted to be general editor of the task force that wrote To Be a Christian: An Anglican Catechism, a 160-page document which was approved in 2014 by the College of Bishops of ACNA. He was awarded the St. Cuthbert’s Cross at the Provincial Assembly of ACNA that year by retiring Archbishop Robert Duncan for his “unparalleled contribution to Anglican and global Christianity.”

By late 2015, due to his failing eyesight, Packer was no longer able to continue writing or travelling. Still he regularly attended the early Sunday morning Eucharist at St John’s and afterwards the Learners’ Exchange, where he was often a presenter.

Just a few days after suffering a fall, Packer died peacefully in hospital with Kit and their priest at his bedside. Kit said she can’t imagine life without her husband. He died on their 66th wedding anniversary and she commented that it was “like Jim to make things convenient for me. I won’t forget which day he died!”

Just days earlier Packer had been asked which of his books was his favourite or which he considered his most influential. He replied,

“I don’t think about my books in that way. In all my writings I wanted to bring people to Jesus so that they could know the forgiveness of sin and be grateful.” Packer repeatedly returned to the theme of gratitude saying, “I want to see the world transformed by gratitude for the forgiveness of sins.”

University of British Columbia historian Dr. George Egerton considered Packer “a dear friend and mentor” and said of him:

“He was famous and revered for his best-selling books, but was utterly without pretensions. He had time for anyone. If you needed an article for a journal, or a review, he was always happy to oblige. He loved conversation, and had an eager eye and ear for the absurd and comic, not least from within conservative Anglican circles. He knew his sermons were sometimes too long and a bit dry but he could make them memorable. Once at St John’s, when seeing a few too many heads nodding off, he shouted out ‘sex,’ and then smiled and quietly resumed, noting he now had everyone’s attention.

“His Christian legacy is enormous and global, as apologist, defender of Anglican biblical fidelity, tremendous organizer, and mentor to countless readers and friends. It brings me joy to think of his entry to heaven, to be greeted by his Lord, and the Heavenly Hosts, and that great cloud of witnesses, who have gone before — especially John Owen, Richard Baxter and John Calvin. What a conversation!”

Alister McGrath, himself an evangelical Anglican theologian, has written a biography of Packer: To Know and Serve God: A Life of James I. Packer (1997) while Leland Ryken has authored a more recent biography: J. I. Packer: An Evangelical Life (2015).

Packer is survived by Kit; their three children, Ruth, Naomi, and Martin; and two grandsons.

Regent College has established the J.I. Packer Scholarship in his honour. Packer’s final work, The Heritage of Anglican Theology, will appear in 2021.