Tribute: Duke Vipperman 1950-2020

Remembering a remarkable reboot and the priests who made it possible

By Sue Careless

THE PRIEST who famously rebooted a struggling Toronto church two decades ago has died. The Rev. Canon Dr. Duke Vipperman passed away on Jan. 3rd at Hospice Wellington in Guelph, Ontario, after a nine-month battle with cancer. He was just shy of his 70th birthday.

The gifted preacher, pastor and mentor will probably best be remembered for leading a remarkable reboot of a dying church. We will examine it here in some detail in the hope that it will continue to serve as a model for others.

In the 1940s, 700 people would gather for worship at the Church of the Resurrection on Woodbine Ave. in East York. But by 1999, only 57 worshippers, most of them seniors, sat in the pews.

Yet in just one day, Jan. 28, 2000, “the Rez,” as the church was fondly nicknamed, received an infusion of 72 new members. And Sunday School attendance jumped from two children to 25.

Ada Sneddon, who has since died, said at the time of the reboot that the small congregation before the sudden change was “dedicated to Christ, to the church, and to one another. But we wondered how long we could stick it out.”

In the previous fall the Rez had called Vipperman, who was then an assistant pastor at Little Trinity, a larger downtown Anglican church, to be its new pastor. In an unusual move that had the blessing of his bishop, Michael Bedford-Jones and the incumbent of Little Trinity, the Rev. Chris King, Vipperman invited members of Little Trinity to come with him and 60 did. And a dozen former Little Trinity members also came, for a total infusion of 72.

This was not a split, but a carefully planned, intentional church ‘graft’ between two evangelical Anglican congregations. Little Trinity, a commuter church with 600 on the rolls and an average Sunday attendance of 381, also supported the project with $15,000 over 5 years – with no strings attached.

Vipperman initially told the selection committee that perhaps 10 people might come with him. Then he reflected on the biblical story of Nehemiah, who asked for a tithe of the people to repopulate Jerusalem. So he upped his expectation and ventured that 40 might consider it – but he stressed that he could not guarantee any would.

Then in November of 1999 when Vipperman and King jointly presented the “exodus” proposal to the Little Trinity congregation they asked them to consider several factors: “Do you live within 15 minutes of Woodbine and Danforth (where the Resurrection is located)? Do you sense a ‘divine dissatisfaction,’ that you have gifts that are being under-utilized at Little Trinity? Could you work well with the new incumbent?”

On Jan. 8th, people considering the move met with members of the Resurrection for a day of preparation and to hear from one another.

A week later, 400 people packed Little Trinity for a commissioning service for the 72 leaving. Vipperman had served there for 9 years, but some who were leaving, including his wife Deborah, had called Little Trinity home for more than 20 years.

Vipperman envisioned a “Velcro” congregation that could attract a blend of ages and life stages so that visitors sensed they could “stick.” People in their 30s will attract first-time home buyers. Families with children would attract other families with children.

The priest admitted it would be a challenge to attract new members, particularly those 25-45 years old, an age group that shows resistance to institutions.

Even though about 68 percent of the local neighbourhood claimed to be Christian, no more than 12 percent attended church. The local Presbyterian church had closed just months earlier.

“Other capable clergy served other churches in this area and have not seen their dreams realized,” he said. “I cannot do it alone. I sense a dramatic growth to be possible but only with dramatic initiatives.”

Murray Moerman, a strategy director at the time for the national church planting organization, Outreach Canada, commented: “The more radical the restart, the higher the rate of success will be, even though there will be some element of conflict. If the incoming group had been only one-quarter the size of the ‘old guard’ I doubt it would have worked. And the new group has to be given a great deal of latitude. A restart situation such as a radical infusion is best done by old and new having a clear understanding of their expectations.”

Moerman said it would be three years before such a church graft could be deemed a success. After only six months, two dozen other neighbours had joined. Five years after the reboot, Resurrection had 220 worshippers weekly, many from the neighbourhood.

Jim Pike who, with his wife Marilyn, made the transition said, “Everyone moving made a decision and you get an intentionality and energy with that. Whether you know each other or not, it creates a terrific bond. We don’t know how it will play out. Only God knows. We have a sense of adventure and we’re along on the ride with God.”

Did the Resurrection’s original congregation fear being overrun by the newcomers and losing its identity?

“We are not the same church we were ten years ago or two weeks ago, said George Gurr, who was a church warden at the time of the graft. “Identity changes for churches just as it does for people. But we have not lost our core identity, our faith in God. That’s all that really matters.”

“One of the best ways of building trust with urban people is to identify with them and join them in solving needs,” Vipperman said. “I want to live in the community. I want to be meeting neighbours, getting a sense of our community and sharing its concerns.”

Vipperman embarked on a door-to-door canvas with no mention of money. Church members simply asked their neighbours what, if they were to attend church, would appeal to them and how the church might better serve them.

For instance, in 2012 the church transformed its south lawn into a full-scale community garden, inviting members of the congregation to garden alongside neighbours. (Plots were allocated 50/50 between parishioners and neighbours.) The project now has 37 active gardeners, and is a neighborhood hub for BBQs and picnics.

Today, twenty years after the graft, new members easily outnumber the “old guard” and the “transplant” people combined.

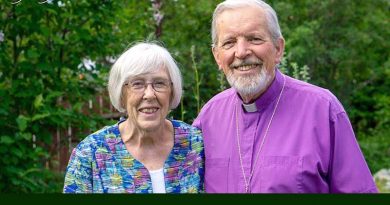

After 17 years of ministry at the Rez, Duke retired (or in his words, “rewired”) and with Deborah settled in Fergus, Ontario. From there he helped other churches reboot, most notably Trinity, Durham and also continued to be a sought-after mentor to many parishes, having been a Missional Coach for the Diocese of Toronto.

It took courage for Vipperman and his family to lead the exodus not knowing if anyone would follow them, but also for King to be willing to let a sizable portion, ten percent of his own flock, go – a portion that included some of the next generation of lay leaders. But it was a risk King was willing to take.

Remarkably over the next two years the empty pews at Little Trinity did refill with new members. King said, “As a pastor it was a privilege asking the whole congregation to consider the move, to pray, to listen, to be attentive to God.”

Born Walter Bryce Vipperman in West Virginia in 1950, Duke was a teen during the turbulent 1960s. A would-be rocker, philosophy major and occultist, he was once called “the freakiest man” evangelist John Guest had ever met.

In 1971 he responded to an invitation to make Christ the Lord of his life and so began a gradual but radical transformation. He first became janitor at Guest’s church in Sewickley, Pennsylvania and avidly absorbed the Christian teaching he received there. He did youth ministry in Pittsburgh, Quebec City and Fairfax, Virginia.

In 1981 he married Deborah, a Toronto physiotherapist. Afterward they both studied at Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry in Ambridge, Pennsylvania. There he earned a Masters of Divinity and later a Doctor of Ministry. His doctorate focused on church planting successes and failures in Toronto from 1990 to 2005.

Ordained in the Diocese of Huron, Vipperman served as an assistant curate at St. George’s, London (1983-86) and then as rector in a two-point rural charge in Exeter and Grand Bend (1986-1990). He served at Little Trinity Church for nine years (1991-1999), first under Rev. Peter Moore, then as interim priest-in-charge until Chris King was appointed. He worked with King for three years before Little Trinity sent him to reboot the Rez.

Vipperman was a founding member of Barnabas Anglican Ministries and Fidelity, a Chaplain in the Church Army, a Vice-Chair of Barnabas Anglican Ministries and a member of the National Essentials Council. He was a companion of the Northumbria Community, and helped found its local expression in the “Carrying Place.”

He was also a fine musician and enjoyed playing not only guitar, but also pandori and sitar. He played the sitar for Yeshu Satsang, an East Indian Christian fellowship. In return, Yeshu Satsang provided Hindi music at his funeral.

That day the church he had rebooted was packed to overflowing with not only parishioners from his various flocks, but also a strong showing of fellow clergy.

Vipperman had requested that the Rev. Anna Spray, who had been his pastoral assistant at the Rez and who now serves in an Anglican Network church in Victoria, preach. And she did so with gusto, urging the congregation not to be simply “silent witnesses” to the gospel but to take “holy risks” as Duke had done.

Duke Vipperman is survived by his wife Deborah and their three adult children: daughter Donovan (Ross), and sons John (Danielle) and Michael, and grandson Connor. He died surrounded by his family while listening to “It is Well with My Soul.” TAP

*************************************************************************************************************

“God blended us together, the original congregation and the transplants, plus many new people who came, to be a more relevant, mission-minded church. Though often more art than science, we applied the best in Church Planting thinking to shift our church culture to better reach our neighbours…. Many churches could use our model. A larger church (200 and above) could send people to help a smaller one turn around if:

1) they share a theological outlook

2) there is a population near the receiving church that can be reached

3) they are determined to love each other over the long haul, and

4) they are willing to adjust how they sing, worship and “do church community” to converge with what their neighbours respond to.

“Rapid growth presented challenges and blessings…. It was hard but it was worth it.” – Duke Vipperman, writing in 2005. TAP